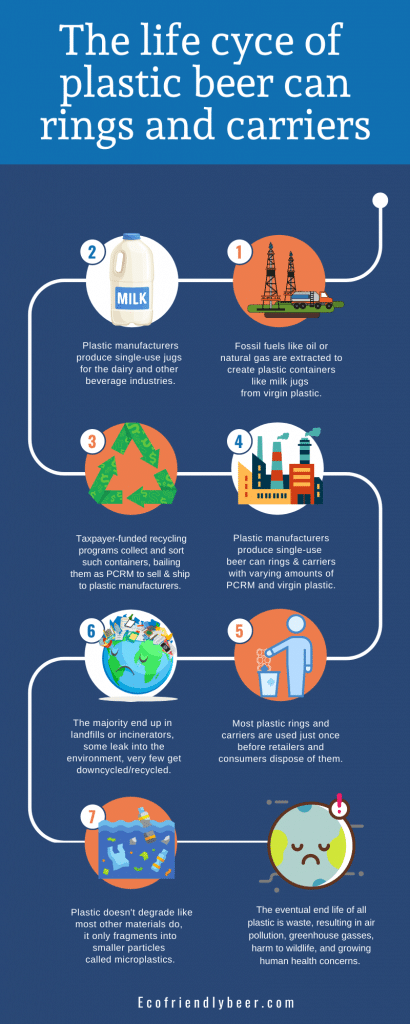

A look beyond the marketing claims of most plastic manufacturers begs a deeper question: ask not whether plastic products are recyclable, ask whether those products actually get recycled. When it comes to those flimsy 6-pack rings or rigid carriers that conveniently bind your beer cans together, the unfortunate answer is not so much. Considering the plastic pollution crisis the world is dealing with, and that many craft drinkers lean toward being eco-conscious, it’s puzzling that so many craft breweries continue to adorn their products with unsustainable, single-use packaging. There seems to be a disconnect, or perhaps some marketing spin (something the plastics industry is really good at) at play .

Marketed as “100% recyclable” by their manufacturers, those flimsy 6-pack rings and rigid can handles are anything but in reality. The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection’s RecycleSmart website says “cut up rings to protect wildlife and put them in your trash bin.” In St. Louis, the city’s recycling program advises residents “not to put rigid can carriers in their curbside bins.” It’s the same story in Arizona, Illinois, Connecticut, Michigan, Virginia, and just about every other state in the U.S.. according to an official from Waste Management, the largest trash and recycling company in the country. Part of the problem is their shape. In the recycling industry they’re known as tanglers because they can wrap around the machinery and gum up the works. And because they’re flat, they often get missorted and end up contaminating paper and cardboard processing. The popular black ones can’t be sorted by infra-red scanners because black is undetectable to automated sorters. Ultimately, most end up going to the landfill or incinerator.

Is a product really recyclable if no one’s able to recycle it?

As for the recyclability claims stamped on most plastic products, that’s a fantasy. As a 2017 study on the fate of all of the plastic ever made has pointed out, a mere 9% of the pervasive material has ever been recycled. Single-use packaging like beer can rings are assuredly recycled at an even lower rate than that. And of those, most are actually downcycled into lower quality material used to produce other inexpensive and unrecyclable goods. A conservative estimate is that less than 5% of can rings/carriers are ever actually recycled into new rings or carriers. The familiar if a tree falls in the forest thought exercise sums it all up effectively: if you claim to have produced a recyclable product, but there’s no one there to recycle it, have you really produced a recyclable product? Again, the unfortunate answer is not so much.

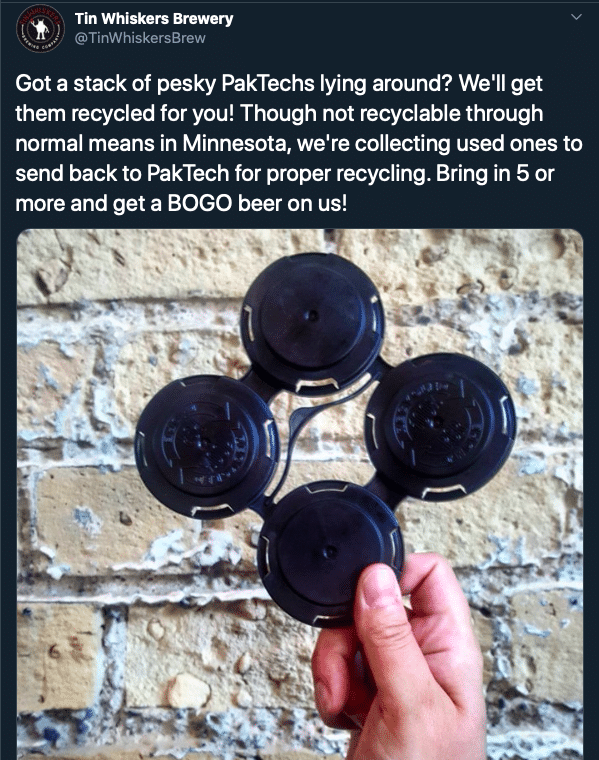

Hi-Cone and PakTech, two of the largest players in the can packaging industry, have responded to concerns about the recycling realities of their products with largely impractical recycling schemes that require breweries, retailers, and consumers to shoulder most of the responsibility. The former offers a free mail-in program that allows for rings to be sent back and presumably recycled into new ones made with 50% PCRM. PakTech’s version consists primarily of shipping a branded plastic collection bin to any brewery that requests one. So far, a few hundred have taken them up on the offer, but PakTech supplies carriers to well over 5,000 breweries in the U.S. alone. For most, that’s where the relationship ends. It’s up to the breweries to arrange and pay for a reprocessing company to haul their collected carries away to be downcycled. PakTech’s website lists only a few dozen such companies in 20 or so states that are currently doing so.

To their credit, hundreds of breweries around the U.S. have taken it upon themselves to make such arrangements, with some even incentivizing consumers to bring their carriers in by offering free beer. But breweries shouldn’t be saddled with product stewardship for highly profitable, multi-national companies. Instead, manufacturers should implement fully funded take-back programs as part of their extended producer responsibility (EPR). Breweries, for their part, can demonstrate corporate social responsibility (CSR) with outside-the-box thinking that identifies less environmentally harmful packaging solutions and begin transitioning toward them.

Among the best practices that breweries have employed for decreasing their reliance on plastic packaging are switching to compostable or paperboard-based can carriers, using cardboard flats (boxes) without carriers when selling out of their taprooms, or accepting take-backs of plastic carriers and then sanitizing and reusing them to packager their beer. Such decisions go a long way in ensuring that the environmental concept of reduce-reuse-recycle is being followed in its intended order, and that trading the convenience of single-use plastic packaging for a greener and healthier planet is worth it. Here’s a rundown of how to avoid using new plastic carriers all together, and in some cases, save money in the process.

No packaging at all: Don’t laugh, but for breweries selling beer out of their own taprooms it’s possible to do it without any packaging at all. California’s Pure Project Brewing requires consumers to bring their own reusable bags, portable coolers, or even saved can carriers for takeaway purchases. This requires the brewery to sell loose cans (a wildly popular retail option among consumers), but the upside is zero packaging waste associated with on-site sales of their beer. “You can change consumer behavior by telling a better story,” says co-founder Mat Robar, “using plastic carriers is just a habit but there are ways we can adjust to do better by the environment. No packaging when possible, or as sustainable as possible when needed, is the goal and we think it’s worth the effort.” Ontario, Canada’s Henderson Brewing has even found a way to deliver its beer without any packaging, having successfully piloted home delivery to consumers in durable, reusable milk crates. It’s a widely used practice in Europe according to co-founder Steve Henderson, who has 1,500 crates in circulation between consumers and restaurants/bars and says it’s saved his brewery considerable money.

The least amount of packaging possible: The functional replacement of plastic rings or carriers with less packaging is a strategy employed by some of the top rated breweries in the country, including Tree House and Hill Farmstead. They sidestep plastic by providing customers with corrugated cardboard boxes that hold up to 12 or 24 cans each, and are universally accepted in residential recycling programs. They’re even durable enough to be returned or re-used multiple times as long as they aren’t exposed to too much moisture. By choosing not to use plastic carriers, Tree House, Hill Farmstead and others are sending a message that the convenience of single-use, throw-away packaging isn’t worth the cost to the environment.

The most sustainable packaging: In instances when single-use packaging is a necessity, such as with third-party distribution, the most environmentally sustainable option currently available is compostable packaging. A pioneering product, and one that is quickly gaining traction among eco-minded breweries, is the Eco 6-Pack Ring or E6PR. First made popular by Florida’s Salt Water Brewery and now being used by hundreds of breweries worldwide, Eco Rings are made from only organic plant materials and are therefore completely biodegradable and truly compostable. Vastly improved since initial introduction a few years ago, they hold up well to distribution demands (including moisture) and unlike their plastic counterparts are no threat to wildlife or the environment because of the closed-loop lifecycle design. The product’s ideal end-of-life destination is a commercial composting facility, but if discarded on land (including a backyard compost bin) or in water will typically biodegrade within a few months.

Sourced from farm industry by products (specifically, the unharvested portion of wheat stalks which are otherwise left in the field as waste), the upcycled biomass material will eventually degrade into organic compost that doesn’t pollute its environment. Implementation factors for the Eco Rings include its cost and its application. As with most innovations, cost is marginally higher than its unsustainable plastic competitors, though it is expected to gradually come in line with them as the manufacturer scales up production. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that that craft beer drinkers are willing to pay a premium for sustainably produced and packaged brands. Application logistics for the E6PR will vary for breweries depending on their level of production. A bit less pliable than plastic, they require a different application method than plastic snap-ons, which you can see in the video below (high speed applicators, including automated machinery, is also available for faster canning lines).

Cardboard and paperboard packaging: For larger breweries that sell beer in multi-packs of 12 or more, cardboard wraparound packaging is a common and more sustainable alternative to plastic because of its high rate of recyclability and better biodegradability. The expense of automated machinery required for wrapping and sealing such packaging is cost prohibitive for most microbreweries, however. Attempts thus far at less expensive, smaller-scale paperboard packaging have proven less effective than traditional cardboard. Fishbone initially developed a commercial can carrier but had issues with performance when it was exposed to moisture. They have since improved the product. WestRock introduced the CanCollar, a laminated paperboard carrier that performs considerably better but is neither fully biodegradable nor easily recyclable. Its wet-strength polymer (plastic) CarrierKote material is laminated to the paperboard to protect the carrier from moisture and rough handling, but such multi-layer material (specifically the plastic) decreases its recyclability rate because of the limited sorting capabilities of most materials recovery facilities (MRFs) they end up in.

Take-back programs to re-use or recycle plastic carriers: While phasing out the use of plastic carriers is the most sustainable choice, there are ways to at least limit their negative impact on the environment if breweries are willing to take extra measures. That’s what Untold Brewing in Massachusetts decided to do. “We’ve been reusing them from the get-go,” said co-founder Kyle Hansen, whose taproom in Scituate has a collection bin for recycling plastic can carriers but struggled to find a place to send them to when it was full. Instead, the environmentally-minded brewery decided to reuse them as many times as possible before eventually discarding broken ones. It even partnered with specialty store Craft Beer Cellar to accept its glut of extra carriers too. The end result has been a little extra work to sort and sanitize the carriers, but the cost savings of not having to buy new ones, as well as the avoidance of the environmental guilt, has more than made up for it according to Hansen. Unfortunately, the norm for the majority of breweries is to use a new plastic carrier for every 4 or 6-pack they package, essentially making it a single-use item. In rare examples, diligent breweries have arranged for collected PakTechs or Hi-Cone rings to be shipped back to the manufacturers and recycled into new carriers, but it’s the exception and not the norm within the industry.

Given the dismally low rate of recycling for plastic in general (which is even worse for problematic items like can carriers), as well as the environmental and economical consequences associated with plastic waste, it’s hard to justify choosing such an unsustainable option compared to the existing alternatives. As the Brewers Association (BA) has pointed out, there is growing interest in sustainable production and packaging within the industry, and craft brewers, especially microbreweries, have substantial room for improvement. Furthermore, research shows that craft beer consumers value sustainable business practices and are willing to pay to support such efforts. For some breweries such environmentally conscious decisions and the associated social-cause marketing efforts that can be associated with them can even be a differentiator for their brand, especially among the growing number of eco-conscious consumers.

To be fair, beer can rings and carriers aren’t the biggest culprit in the tsunami of worldwide plastic production and its ensuing global pollution crisis. But they are a contributor, along with dozens of other examples of pesky plastic packaging that consumers have unwittingly grown accustomed to. But change can happen if we pay closer attention to our everyday decisions. As studies have revealed, eliminating the use of unnecessary packaging or switching to truly compostable options have the potential to cut plastic waste by nearly half. It’s about taking a closer look at what we put into our recycling bins, which is often just wish cycling. If that’s the case, and it nearly always is with plastic rings and carriers, then speak up for better packaging options, and choose from the growing number of beer brands that have ditched plastic packaging to show they value the environment as much as their profits.![]()

About Eco-Friendly Beer and this publication

Ecofriendly Beer Drinker recently received a Graduate Certificate in Environmental Studies at the Harvard Extension School. He has researched and written extensively on plastic packaging and the craft beer industry and considers this publication to be an informal white paper (an authoritative report that informs readers concisely on a complex issue). References to any of the facts contained in it, as well as answers to any questions related to but not specified in this post, are available by request via ecofriendlybeerdrinker@gmail.com. This paper’s goal is to provide a factual overview of can packaging options from an environmental sustainability perspective, and in so doing inspire change for the better within the craft beer community.

One limitation of this overview is that it doesn’t rely on a life cycle assessment (LCA) of each can packaging option, and therefore it cannot definitively compare them from an energy or carbon accounting perspective. That said, a well documented criticism of LCA is that such analyses do not take into account renewability of energy flows or toxicity of waste and their affiliated harm to nature, wildlife, and human health.

Related: Do These 3 Things to be an Eco-Friendly Beer Drinker

Strong work, thank you!