You’ve likely heard it before: brewing beer leaves a large carbon footprint. It’s one of the reasons why larger regional brands often make massive investments in renewable energy, wastewater treatment systems, or even carbon recapture technology to offset some of their environmental impact. But what can a smaller micro brewery do, especially one without deep pockets? As three eco-inspired Massachusetts breweries have demonstrated, you’d be surprised.

When Mike Pasalacqua launched Harper Lane Brewery nearly three years ago, one of his priorities was to start an eco-friendly brand without investing too much up-front money. So he did something practically no other brewer was doing at the time – packaged his off-premise retail beer in growlers. “It was the only profitable option given the small scale I’m brewing at,” he explained, referring to his 2-barrel nano operation. “The cost of a canning line, or even mobile canning, wasn’t practical.” The decision turned out to be a win-win, allowing Pasalacqua to sell his beer at high enough margins while providing environmentally conscious consumers with a refillable option for take home beer. “The novelty of a growler next to all those cans on beer store shelves these days hasn’t hurt either,” he says. Not only has it helped distinguish his brand, he believes, but It’s helped him develop a loyal customer base in the liquor stores he self distributes to.

In addition to being an economic and eco-friendly method for packing takeaway beer, refillable growlers allowed Harper Lane to continue selling its beer through the Covid-19 pandemic when keg sales vanished overnight. “I’m in the process of building a new growler-filling machine and expanding that side of the business,” says Pasalacqua, who prior to the crisis sold more than half his beer in keg format. The hope is to one day have a brick and mortar space of his own, but for now he’s brewing his beer under an alternating proprietor relationship with another brewery. A model built on what economists and environmentalists refer to as the sharing economy, the agreement allows him to share a brewhouse by mashing in at times when it would otherwise be idle, and to rent unoccupied space for storing his fermentation tanks, glycol chiller, and kegs.

The arrangement is different than that of being a contract brand, notes Pasalacqua. “It means that I’m a fully licensed brewer who brews my own beer, not just someone who pays to have a recipe produced for his brand.” Such a best-of-both-worlds scenario allows him to have full control over the creative process while enabling both breweries to save money on expenses by leveraging economies of scale. With much of that savings Harper Lane has been afforded the luxury of sourcing ingredients from smaller local suppliers and maintaining its own small-scale hop farm, which Pasalacqua says accounts for at least a third of his hops usage. On land owned by both himself and a neighbor, he’s able to grow half a dozen varieties which he hand picks with his family during harvest season.

Taking into account the supply chain of ingredients a brewery relies on is something Steve Sanderson also takes seriously. Founder of RiverWalk Brewing in Newburyport, Massachusetts, he says they’ve taken a hard look at everything that impacts their efficiency in the brewhouse, from where they source ingredients to minimizing the amount of raw materials used during the mash-in. “We’ve even examined the practice of using massive amounts of hops, which is actually quite wasteful,” he points out. It’s all part of what Sanderson says is the company’s mission to be responsible to the larger community as well as to the planet. He too is part of the sharing economy, increasingly offering contract brewing services to smaller, taproom-focused breweries. In so doing, the benefits of his brewery’s efficiency practices, which range from production to packaging to cold storage, are magnified exponentially.

RiverWalk’s most tangible eco asset, however, and the one it’s most known for, is the the 292-foot high, 600-kilowatt wind turbine that helps power its brewery. “It’s a pretty clear sign to everyone that we’re environmentally conscious,” says Sanderson. In combination with the 500-kilowatt solar array on the roof the brewery, the building generates so much renewable power that some of it is sold back to the grid, a major draw when Sanderson was searching for a new space to expand into a few years ago. Known as the Mark Richey Building, the carbon emissions it prevents annually is equivalent to removing 200 cars from the road.

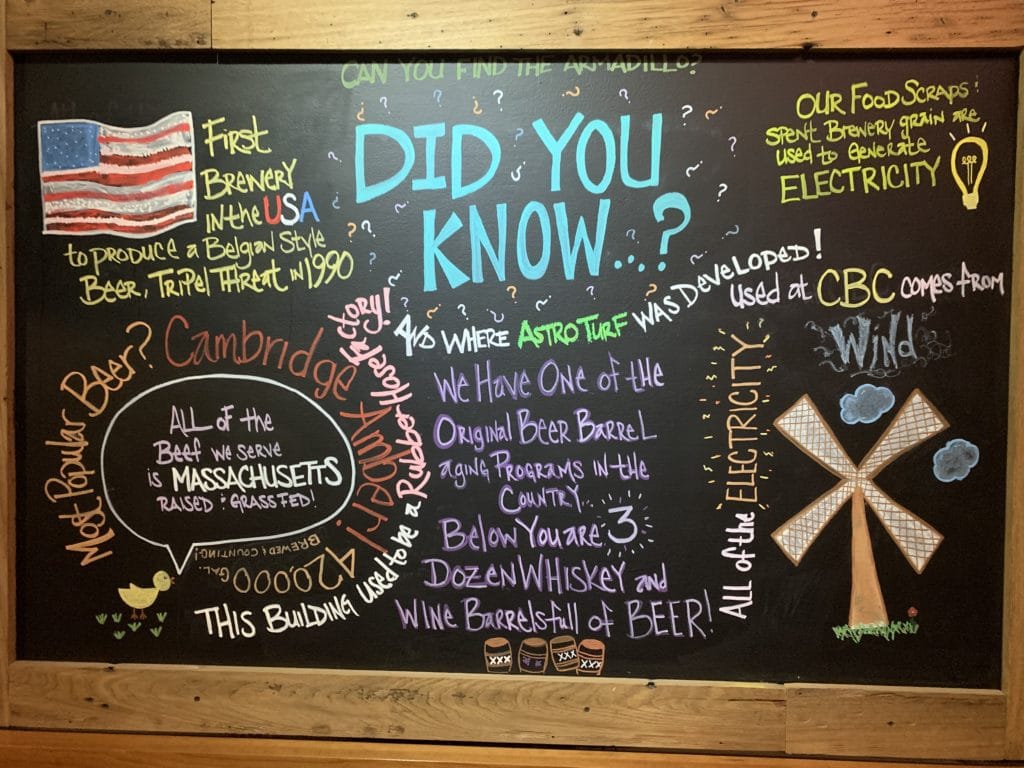

Installing renewable energy on his brewpub’s rooftop wasn’t an option for Phil Bannatyne, founder of Cambridge Brewing Company, so he did the next best thing. “Our electric supplier, Constellation Energy, has an option where you can select 100% wind-generated energy as your source choice,” he explained. “It costs a little more, but I think supporting renewable energy development is important.” Rather than paying for electricity that’s sourced by the local utility and generated by fossil fuels, he purchases what are known as Renewable Energy Credits or RECs. Available for anyone through third-party suppliers like Constellation, it allows environmentally conscious businesses to decrease their carbon footprint even if they can’t access an on-site wind turbine or solar panels. Long a proponent of sustainable practices, CBC was also an early adopter on converting to energy-saving LED lights, full-on recycling, environmentally safe cleaning agents, compostable paper products, water-saving methods at the brewery, and even encouraging employees to bike to work.

How CBC diverts food scraps and spent grains that would otherwise end up in landfill is another impressive story. “We use a Maine-based company called Agri-Cycle which regularly picks up our food waste in these large totes,” says Bannatyne. “They have a number of huge bio digesters that capture methane from bacteria that are decomposing the waste, then the methane is burned to generate electricity.” According to the Agri-Cycle website, its anaerobic digesters also produce fuel, fertilizer, and other beneficial products to “bring food full circle.” It’s a concept CBC’s brewmaster Will Meyers even incorporated into a unique offering he once brewed. A tart session beer called Grateful Bread, and made with leftover loaves delivered to CBC by non-profit food rescue Lovin’ Spoonfuls, it’s aim was to help raise awareness about food waste.![]()

![]()

Please Take Our Beer Drinker Survey